A friend recently posted on Facebook:

“Seriously – if I don’t get this anxiety under control, I am going to be exhausted for the rest of my life.”

I related to her posting:

Anxiety. Fear. Exhaustion.

Within a day, she posted again:

“I try really, really hard to have faith in humanity, but it’s becoming increasingly difficult. Decent people get bad things they don’t deserve, while horrible people get good things they don’t deserve. The universe just seems pretty upside-down to me at the moment.”

Anxiety – Fear – Exhaustion. Now we add Frustration and Confusion to the list.

Can you connect? I can.

Why is the world so unsettling now, we wonder. Jesus addressed our concerns.

“I have told you all this,” Jesus said, “so that you may have peace in me. . . Take heart, because I have overcome the world.”

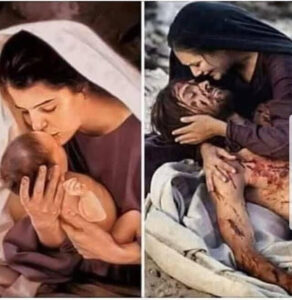

You see, Jesus is speaking to His disciples, having recently entered Jerusalem, the city he so loved, between what we refer to as Holy Week. Similar to the holiday time we are presently celebrating.

“I have told you all this, so you may have peace in me.” Jesus said.

What is “all this” we might question.

We find “all this” in the book of John, Chapters 12-16. In the few days after entering Jerusalem,

Jesus predicted His death, washed His disciples’ feet and told the people He did not come to judge the world but to save it.

He predicted His betrayal and Peter’s denial.

He brought a new command: “Love one another.”

He comforted His disciples, and promised the Counselor, the Holy Spirit to them.

He said, “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.”

He explained that He is the source of life, being the true vine.

And several times He told them to ask for anything in His name and it would be given them.

He told them that the world would hate them but that someday their grief would turn to joy.

It is in this context that He tells them,

“I have told you all this (all these things), so that you may have peace in me. In this world, here on this earth, you will have many tribulations, troubles, trials, sorrows. But take heart because I have overcome the world.”

Some of you now feel like his disciples felt at that time – hated by the world, by your family, your co-workers, your congregation. Some of you perhaps have prayed for a loved one for ages without seeing results. Your heart is troubled. Maybe you’ve received bad news. Or you are afraid. You feel separated from the true vine. You are lonely. You can’t imagine your grief ever turning to joy. The world is “upside down.” Life isn’t fair. But Jesus tell us that we can have peace in Him. He tells us to take heart. He has overcome the world.

You might question why Jesus said, “In this world you will have many troubles” instead of just make everything perfect?

Well, He did!

“In the beginning . . .” we read. “And God saw that it was good.” God was pleased with His creation. It was perfect.

God did not create sickness. He did not create addiction. He did not create death. God’s plan was not for us to suffer. He didn’t create hatred and strife, wars and destruction. But it happens. Because “Here on earth,” or “In this world,” as some translations read, actually in the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve, in their sin, turned the keys over to Satan. For a time, our enemy Satan, roams about, trying to steal from us and kill us and destroy us. (Be sure to read John 10:10 to discover who brings evil and who brings good.)

Was this “upside-down” world God’s original plan? Did He bring it? No. Does He allow it? Yes, He allows Satan to roam ~ because man chose it.

Our Jesus knew it would happen. Our “upside-down” universe is not a surprise to Him. I picture His face saddened as He spoke the words: “In this world, you will have many troubles.” He is saddened that “Decent people get bad things they don’t deserve, while horrible people get good things they don’t deserve,” as my Facebook friend observes. He is saddened that our world, our lives, are invaded by disease and suffering, that our children are hurting, that our world is in strife. He will bring justice one day. But today, we can trust that in Him we can have peace. Peace that passes all understanding, His Word tells us. He has overcome the world. We must trust His Word, for He “has told [us] these things so that in Him [we] may have peace.” I’m so glad He did.

Click here to learn more about the peace Jesus offers.

Please visit me on Facebook (see the “like” icon on this page!

Before we became believers, many of us thought, as the world does, that the gift of salvation was too good to be true – we had to work for it – we had to become righteous by ourselves. So we tried. Of course, we found it to be impossible. The world confuses the two words and their definitions: “righteousness” and “self-righteousness.” The devil pellets the believer with lies, time after time. We hear smug comments like, “You think you’re so righteous, don’t you?” intended to beat us down. And sometimes, they do. If we let them. The devil doesn’t want that word, righteous, in our hearts for even one minute. He hates God’s word. Thief that he is , he immediately comes to steal it from us (John 10:10).

Before we became believers, many of us thought, as the world does, that the gift of salvation was too good to be true – we had to work for it – we had to become righteous by ourselves. So we tried. Of course, we found it to be impossible. The world confuses the two words and their definitions: “righteousness” and “self-righteousness.” The devil pellets the believer with lies, time after time. We hear smug comments like, “You think you’re so righteous, don’t you?” intended to beat us down. And sometimes, they do. If we let them. The devil doesn’t want that word, righteous, in our hearts for even one minute. He hates God’s word. Thief that he is , he immediately comes to steal it from us (John 10:10).